I’ve been thinking a lot about food lately. Food and climate change. Food and chemicals. Foodborne pathogens. Food scarcity. But when I turn on the TV, what do I see? Ads for McDonald’s and KFC. Gordon Ramsay everywhere. When it comes to food, a basic human need, can’t 21st-century television do better than that?

I live in the United States, where more than two in five adults qualify as obese, while at the other end of the scale, one in five children experiences food insecurity. It’s a grotesque juxtaposition in one of the wealthiest nations on the planet – now that has the makings of a TV show!

But honestly, finding food programming that is truly relevant to our times has been hard to come by – until I discovered Lunch ON! on NHK.

This long-running programme is produced in Japan for a Japanese audience, but it is provided by the international service of Japan’s public broadcast organisation, NHK World-Japan. Made available in 17 different languages, the programme can be viewed online as well as in TV markets across the globe.

I’m able to watch an English-language translation of the show on my local public TV station. Voiceover work is provided by a cast of native English speakers, some of whom speak in British received pronunciation, while others deliver their parts in a General American accent.

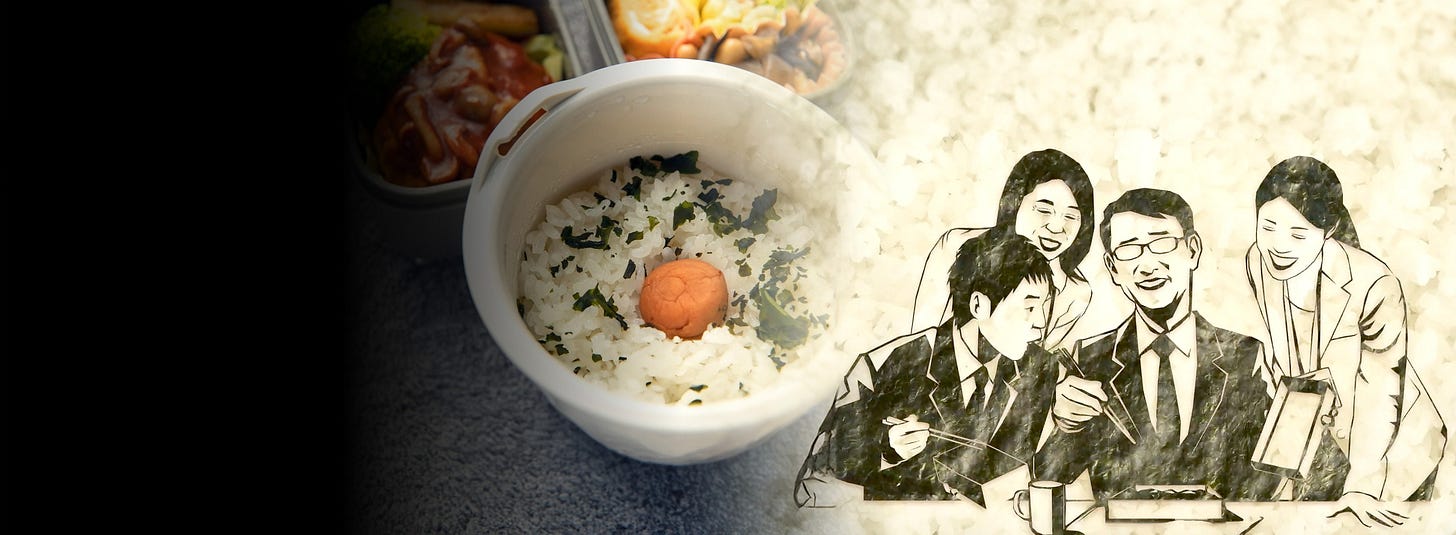

Lunch ON! has been a revelation – a far cry from snarky star chefs, anxious-to-please acolytes, and designer kitchens. Instead, this show provides a veritable bento box, if you will, of emotional, sociological and gastronomic nourishment. While the Lunch ON! premise centres on food, it is seasoned with cultural traditions and workplace visits. It takes viewers throughout Japan to share stories about the lives – and lunches – of the working class.

The show follows a simple blueprint: for every episode, a TV crew tags along with a selected worker or team of workers. Before the programme ever arrives at the central question – what’s for lunch? – viewers learn about who these workers are and what their work entails, thanks to the hand-held POV camera work of the videographer and the inquiries of an off-camera interviewer.

This gives viewers a behind-the-scenes peek at careers they might never have known about otherwise. Auto body workers retrofit luxury cars, for example, and show how they convert them into hearses. (These are high-demand items, given Japan’s ageing population.) The staff at a speciality factory demonstrate how they recycle used egg cartons and remould the material to make daruma dolls. Other recent episodes have featured workers at a golf club factory, drummers in a taiko group, a whetstone artisan, and the captain, crew, and cooking staff aboard a dredging ship.

As co-workers interact with one another in front of the camera, viewers become more attuned to cultural mannerisms and values. And when lunchtime rolls around, the camera ventures into the kitchen where the offscreen interviewer peppers the cooks with questions as they chop, stir and fry. Rice and noodles are common staples. Miso is a prevalent condiment. Vegetables, nuts and greens often are freshly harvested, even foraged.

At larger companies, employees can troop into the cafeteria at lunchtime and select their choice of dishes. But at smaller places of business, workers often bring in artfully-packed bento boxes from home, or pick up a pre-packaged bento from a local grocery. Especially in the more intimate settings at smaller companies, hungry workers often preface the beginning of their meal together with a clap of the hands or by pressing their palms together and uttering a quick “itadakimasu.” A traditional acknowledgement of appreciation for the food, which gets a more prosaic translation in English: “Let’s eat!” Then they pounce upon their lunch in earnest, wielding chopsticks and slurping noodles – only to be interrupted by the intrepid interviewer, who wants to know how they like their meal.

Lunch ON!’s typical run time is about 23 minutes. Episodes contain two feature stories of about 10 minutes each, interspersed with much briefer segments like “Everybody’s Lunch ON!” where viewers send in photos of their own lunches. Sometimes a brief tribute segment called “The Lunch He (or She) Loved So Dearly” honours a cultural icon who has recently died – by remembering their favourite lunch.

Just as Lunch ON! doesn’t shirk from grief, it also acknowledges issues in Japanese society. There’s tension regarding gender-associated roles, for example. An expectation still exists that wives will prepare the bento boxes, but as one segment featuring a retiring paramedic reveals, his wife is resentful about having to rise at 4:30 every morning. On her husband’s final day of work, she is up first, putting together his customary meal of croquettes, pickled greens and rice.

“Retirement from bento-making, too,” she mutters. “And I wish I could retire from being a wife.”

Other sensitive topics come up in workplace conversations. There’s the ever-present spectre of a low birth rate and an ageing Japan. Legacy farms and businesses are in danger of dying out or being abandoned. Venerable artisans have no one to mentor. Climate change gets mentioned. So do natural disasters.

After a 7.8 earthquake struck Noto Peninsula in western Japan at the beginning of 2024, Lunch ON! travelled back to that area to check on a salt manufacturer whose business had been featured on the show 12 years earlier. Mr Yamagishi, now quite elderly, pointed out that since the quake, the shoreline has been pushed out by 100 meters, making it more difficult to collect the saltwater he needs for his salt-making process.

Nonetheless, he is determined to revive his business, even though only a few of his employees have been able to return to help him. Mr. Yamagishi works very hard, and when his lunch break comes, he relishes the bento prepared by – yes, his wife.

“As long as I can enjoy food, that means I’m alive!” he says. “I can still keep going. I’m truly happy.”

Salt of the earth relevance – that’s what we need more of from television’s food programming.

About The Author

Barbara Lloyd McMichael writes on cultural issues from the Pacific Northwest. She has traveled extensively in Japan and written on many aspects of Japanese culture before – tea ceremonies, language schools, gardens, and more. Barbara is a longtime freelance writer, with pieces published in the Los Angeles Times, Fresh Cup, Princeton Alumni Weekly, The Connector, The Seattle Times, Look Japan, Christian Science Monitor, Hollywood Reporter and many regional newspapers in the western United States. Earlier in her career, she worked as a story editor for EMI Films and a story analyst for CBS Television. She lives outside of Seattle in the US.