“Beware the Unknown, fear the Beast, and leave these woods if you can!” These are the Woodsman’s warnings, shouted at the sibling protagonists of Patrick McHale’s Over the Garden Wall at the close of its first episode. Ominous yet mystifying, these words mirror the show’s penchant for hopeful unease, an all too familiar sentiment shared by young adults growing up at an uncertain time. Its popularity among Gen Z viewers is, therefore, unsurprising. Over the Garden Wall’s ability to capture the apprehension and wonder in eyes first perceiving the contours of maturity is its most resonant and terrifying quality. I, for one, can conjure no greater pleasure than its particular brand of annual re-traumatisation.

Every autumn is our first autumn. In mere weeks, brilliant summer days are replaced with an alien season, replete with fiery trees and looming shadows. There’s something unexpected about autumn each time September greets the northern hemisphere —it harkens to the first times we experienced our world as foreign. Its changes are drastic, ungoverned, and wondrous, an ideal stage for mysteries of all stripes, and, in ten short episodes, Over the Garden Wall has cemented itself as a fixture of the beguiling season. Annual rewatches have become as autumnal as pumpkin spice and confronting the realities of climate change. Gen Z’s reverence for the limited series is due, in no small part, to its themes and use of the fall stage; it is, at once, nostalgic and unsettling.

Over the Garden Wall is instantly identifiable as early Americana. The opening treats viewers to a medley of characters before settling on protagonists Wirt and Greg. Hand-painted, canvas backgrounds and an assortment of folks sporting 19th-century colonial garb give the impression of stepping into a painting —it’s an enchanting invitation into the Unknown. Yet, even in its opening moments, McHale is not content merely to introduce the setting and establish future characters. Greens and yellows dominate the pallet of the show, clear signs of autumn, but the lush backgrounds shift to bleak greys and blacks, indicative of a forest unwelcoming of its inhabitants.

Unlike the detailed background work, Wirt and Greg are rendered in simple shapes and primary colours, a duo at odds with the scene in which they’ve been dropped. Before a single word of dialogue, Over the Garden Wall conveys that, amid its beauty, something is amiss. Even the colonial American visual signifiers are contextually jarring. A cart and wagon, drawn by a pair of turkeys and driven by a black cat, a maid in Puritan attire organising a catacomb of skulls, and a sleepy New England harvest festival populated by skeletons dressed in pumpkins. The symbols and fixtures of early American life are attached to odd or unnatural characters and images. This juxtaposition is at the core of Over the Garden Wall’s ethos. It curates a warm feeling of semi-familiarity while lingering on the uncanny. Viewers are invited to take part in its warm autumn allure amidst a cavalcade of peculiar creatures and circumstances. Centralising its narrative around these aesthetic constraints is critical to its conceit; Over the Garden Wall is a call to confront a strange world with childlike optimism and mature wariness.

Structurally, the show is an anthology of sorts. Each episode, save for the final two, is a vignette from Wirt, Greg, and Beatrice’s journey through the Unknown as they encounter the colourful cast of the woods’ inhabitants and dangers. The travellers are passersby in the stories of the Unknown’s denizens, and the odd vignettes in which they find themselves are, largely, the result of indifference to our protagonists. Most characters are concerned chiefly with their own goals and schemes. There’s a great sense that all the characters possess lives and prerogatives that continue well after our travellers leave their company. Such is the skill of an anthology, a continuous reminder that we don’t belong, we’re mere guests in another’s tale.

The anthological nature of Over the Garden Wall doesn’t preclude overarching intrigue or consistent antagonists. Across the narrative, the mysterious “Beast” looms, horned and silhouetted by the shadows of the Unknown, in constant pursuit of young pilgrims who wander into his woods. Often accompanied by the Woodsman, an unwilling accomplice, he seeks to claim the souls of Wirt and Greg and assimilate them into his forest. The Unknown is not merely a fantastical world packed with eccentric characters, there’s malevolence lurking around each corner.

So what, exactly, is happening in this appealing, eerie descent? Outside of allegorizing Dante Alighieri’s longer (and considerably more tedious) allegory, Over the Garden Wall is concerned, primarily with an exploration of “maturity”. Most plainly, Wirt and Greg’s encounters showcase the necessary parity of youthful openmindedness and mature concern. The half-siblings could not be more different. Greg is joyful, curious, creative, silly, intuitive, and naive much in the way we might expect of a young boy. Wirt is angst incarnate. He’s fearful of wrong decisions, his crush, and social discomfort. In short, a teenager. These two butt heads across the limited series as Wirt views Greg as a burden, he is regretfully obliged to keep safe. Yet, often, Greg’s innocent sense of misadventure sets the pair down the right path. His openness and resilience defy a call to submit to this new, impossible world. Wirt isn’t without his merits, his analytical mind and concern for danger are responsible for keeping the pair alive beyond sheer luck.

As the brothers traverse the perils of the Unknown it becomes increasingly apparent that the beast’s pursuit is philosophical in nature. It can’t physically harm them, instead opting to influence unfortunate lost souls to wander eternally in his forest. To keep his lantern lit. To lure others into the despair of an Edelwood transformation. Losing heart on the journey is the characteristic shared by the Beast’s prey and, ergo, it is the only way to “fail” at growing up. Becoming despondent and submitting oneself eternally to directionlessness, amid a strange indifferent world, is the fate that Over the Garden Wall most abhors. No matter how lost and confusing the world seems, we must persist.

The charming aesthetic direction, characters whose names are their professions, and a witch interested in obtaining child servants all land Over the Garden Wall squarely in the camp of modern-day fable. It’s a Grimm’s fairytale for people for whom the prospect of home ownership is equally fanciful. It’s a yarn about growing up in a world full of things you don’t understand, people who are magical and creepy, and an overwhelming sense that giving up on trying to make it out the other end would be easier. It’s a story that could only ever be animated.

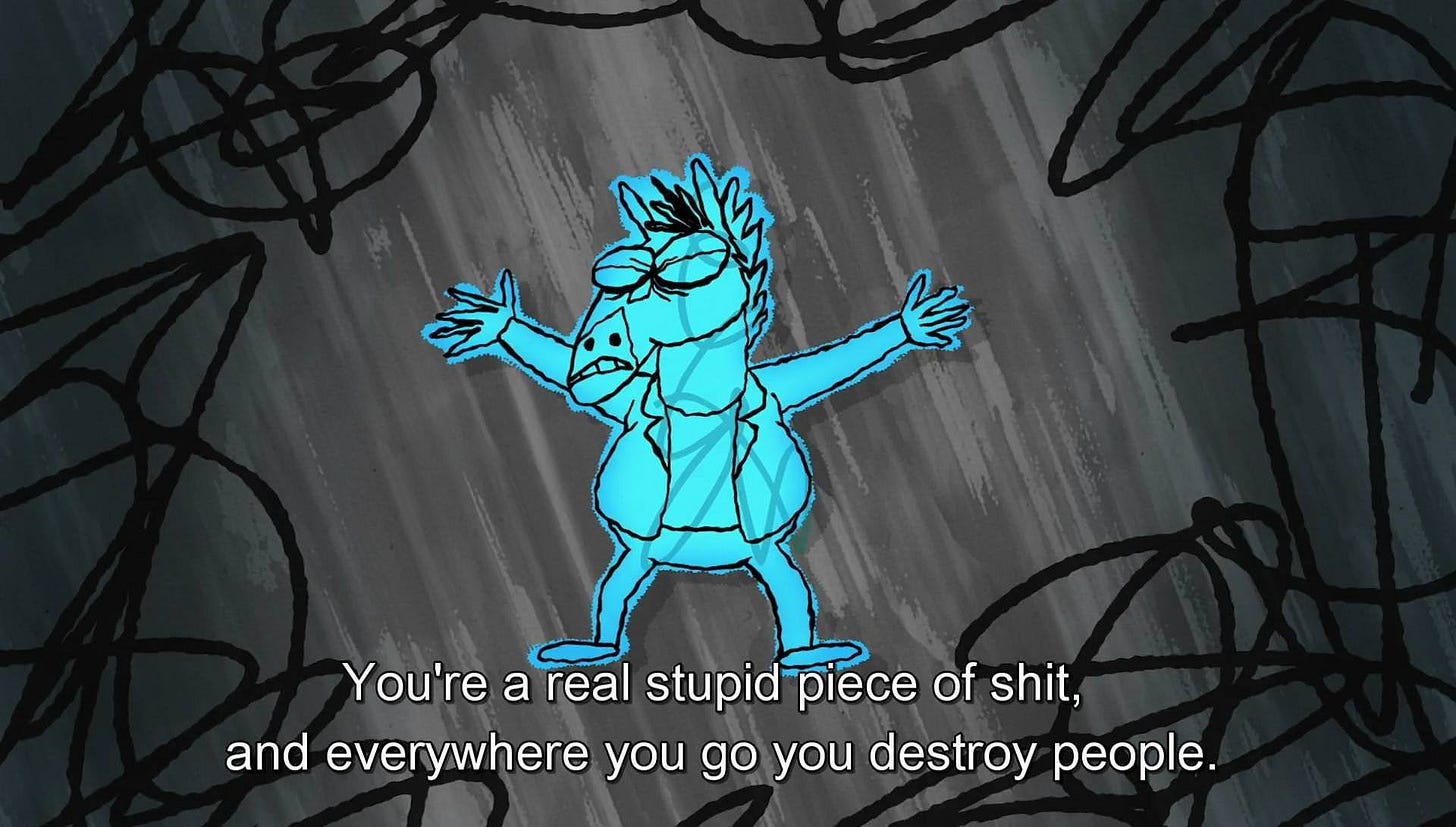

Animation’s capacity for abstract storytelling is immense and underexplored. The animator’s power lies in abstraction. It is by nature, not “realistic”. This lack of proximity to reality enables animators to tell stories whose intimacy is reliant on the truth contained in exaggeration. Bojack Horseman’s depiction of depression through rough scribbling linework will always feel more honest than an actor portraying the mental illness. Hayao Miyazaki’s breathtaking frames of the natural world are almost too beautiful, arguing a truth beyond scenic nature photography about the necessity of its preservation. More to the point, Over the Garden Wall’s unnatural yet familiar tone can only be achieved through a medium that feels like reading a storybook. To say nothing of its ability to portray circumstances entirely untenable through modern visual effects, animation’s capacity for telling intensely interior stories is paramount. Gen Z gets that.

Gen Z’s attraction to the story is fairly predictable. As a generation, they’re far more receptive to the merits of animation than those prior, and their affinity for a past they’ve not experienced is a well-documented phenomenon. Perhaps Over the Garden Wall’s setting represents an extreme version of this imagined nostalgia. What’s more likely, though, is this story resonates with Gen Z in a way other programs don’t. Owing to the ubiquity of the internet from adolescence, Zoomers were aware of far more than previous generations. The inexplicable void of adulthood was made far more confounding, the internet (particularly, the internet of the aughts and early 2010s) was a seemingly lawless cacophony of the world’s knowledge —inscrutable and miserable. Growing up with this awareness is paralyzing, and while many stories champion perseverance through adversity, few take the intimate and introspective tone of Over the Garden Wall. Fewer still, acknowledge the strange mixture of wonder and fear with which teenagers approach the adult world, yet the show takes it in stride.

Beyond its visual intrigue and perplexing setting, Over the Garden Wall reminds viewers that it’s okay to be fearful and confused. There’s nothing wrong with approaching the strangeness of adulthood with childishness and caution. The show’s themes are fundamentally hopeful, and, in a world no less erratic, there’s a comfort in revisiting a program that helped many navigate that peculiarity. We should all make time to beware the unknown, fear the beast, and make it through the woods. Before you know it, it’ll be Winter.

About the Author

Jaedon Abbott is a journalist from New York City based in London. He studied at New York University, and writes media analysis essays and reviews at Fox in the Fields. With a degree in political science and background in philosophy and competitive debate, he values an analytical approach to reviews, analysing modern pieces of media through their arguments and connections with broader trends and other art.